On Monday, 11 December 2017, a panel of 3 judges of the High Court of Lesotho heard argument in the case of Private Lekhetso Mokhele and Others v The Commander, Lesotho Defence Forces and Others. Justices Monapathi, Peete and Sakoane presided over the hearing.

Background

The Commander of the Lesotho Defence Force in March 2016 issued a Standing Order to the effect that any female soldiers with less than 5 years’ service who got pregnant willfully or negligently would be discharged from the force. The applicants, two of whom were married, and one of whom subsequently had a miscarriage, became pregnant and were discharged from military service for willful disobedience of a Standing Order. They were discharged by then Commander of the LDF, Lt. Gen. Kamoli, without being subjected to a summary trial or court martial. The applicants challenged their discharge on the grounds that it was unlawful, unreasonable and irrational because they were discharged without a trial and proper hearing for the purposes of determining their guilt and assessing the appropriate sentence as provided for in the Lesotho Defence Forces Act. In addition, they argued that the Standing Order itself was unlawful as it was contrary to public policy and the common law principles of rationality, reasonableness and legality and that there is no reasonable justification for it.

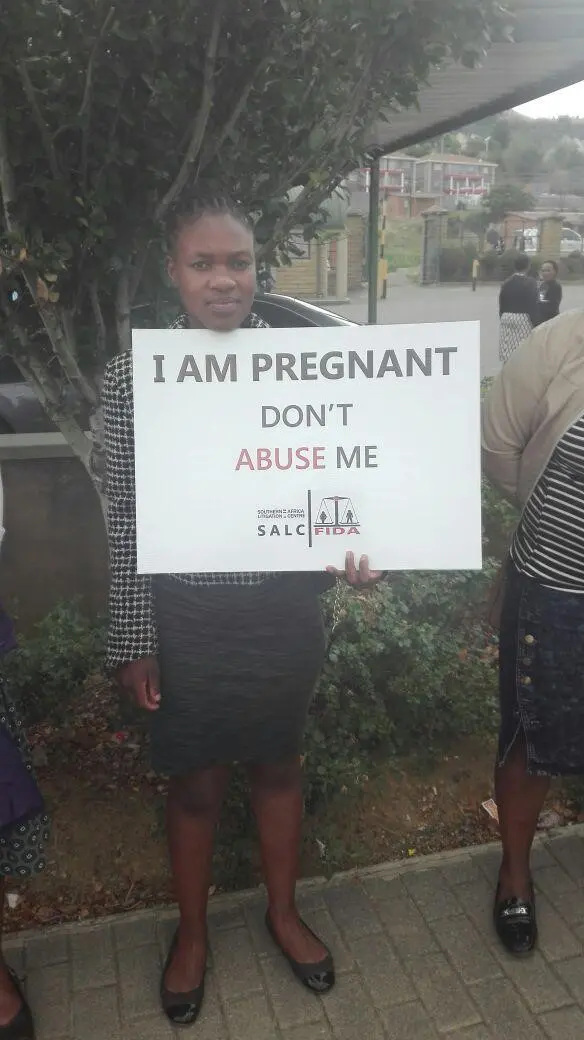

The applicants were represented by Advocate Monaheng Rasekoai, and the respondents were represented by South African Advocate Thembeka Ngcukaitobi. The Southern Africa Litigation Centre provided technical support to the applicants and FIDA-LESOTHO provided advocacy support to the applicants.

Advocate Rasekoai summarized the applicants’ case, buttressing the applicants’ arguments that the Commander had exercised the discretion to discharge given in section 31 of the Lesotho Defence Forces Act unlawfully by not allowing the applicants to be tried by summary trial or court martial, which was required because they were accused of having breached a standing order, which is a military offence in terms of section 53 of the LDF Act. In addition, the Standing Order was communicated to the applicants after they had already been recruited, not before they had joined the army and also the Standing Order itself was not made available to the applicants in writing but just communicated verbally at a pass-out parade after completion of training. He argued that the Standing Order itself was unlawful, unreasonable and irrational because the reasons given by the Commander for its existence and application were unacceptable and objectionable, as the Commander appears to place the army command in loco parentis to the applicants and considers the applicants as persons that were too young to engage in sexual activity, yet at the same time trusting them to handle weapons. Advocate Rasokoai also argued that the fact that the same army provides for maternity leave for pregnant women in the army who have been in service for 5 years or more shows a contradictory stance and the differentiation is not justifiable. A comparative argument was also made, that other countries like Malawi, Zambia and South Africa had put in place maternity policies in the army that were equitable.

The respondents’ major arguments, as presented by Advocate Ngcukaitobi, were, firstly that the Commander was entitled to discharge the applicants in terms of section 31(b) because he was empowered to do so in the best interests of the army for the purposes of army discipline and that it was irrelevant that they could have been charged and tried for the offence. Secondly, he argued that as the case was not a constitutional matter and merely a review, the court should take a narrow approach to the case, meaning that the court was not supposed to look into the appropriateness of the reasons given by the Commander for the policy but that it was enough that the Commander had given reasons that were linked to army purposes and generally, courts ought not to be ready to interfere in military matters beyond asking the army to justify its policies.

The court adopted a very robust approach in the case and posed a number of important questions and observations.

The court raised questions about the lawfulness of the Standing Order itself, and Justice Sakoane raised questions about whether the powers of the Commander to make Standing Orders in terms of section 53 of the Act (for routine matters) extended to making Standing Orders that had the effect of banning female soldiers from the army, observing that the impugned order was not an order of a routine nature. He remarked that in terms of section 192 of the Act, the Minister of Defence has the power to make Regulations and queried whether in fact, the Commander was effectively creating legislation, a function which was reserved for Parliament and the Minister by way of Regulations.

The court also observed that the applicants were alleged to have breached a Standing Order, which was an offence itself, which, as provided for in the Act, attracted a maximum penalty of imprisonment. Justice Sakoane queried why Applicants were not subjected to disciplinary proceedings as provided for.

Justice Sakoane further questioned the basis for the Standing Order, querying whether pregnancy was an ailment and how it would make a soldier unable to carry out their duties, and, if that was the case, why the Commander didn’t proceed in terms of section 24 of the Act which deals with the procedure where incapacity of a soldier is alleged. The court also observed that in the event of inability to perform some tasks due to pregnancy, it would be reasonable to consider assigning pregnant soldiers to other duties that were less demanding, and also granting them maternity leave as is provided in the Regulations. Justice Sakoane noted that in fact the Regulations that provide for maternity leave for pregnant soldiers do not differentiate between any class of women, and, if indeed it was intended to apply only to women who had served for more than 5 years then it should have been expressed in the Regulations.

The court was not amused by the import and effect of the Standing Order, and questioned whether a reasonable commander would find it in the best interests of the army to exclude pregnant women from the army just for getting pregnant.

With respect to the powers of the court in reviewing this case, Justice Sakoane observed that because of the rule of law, whatever powers are given by statute have to be constrained and it cannot have been intended by Parliament to give unfettered administrative power and a court can interfere if it is said that the exercise of those powers was illegal and irrational. Justice Monapathi observed that the court has previously exercised its powers of review even in terrorism cases, with appropriate safeguards. In this case the court noted that the context of the case is that the Commander is saying that women who join the army should not become pregnant and that the army does not need pregnant women, and the question that arises is whether or not that position is reasonable.

The Court has reserved judgment.

Essentially, from the submissions and issues raised at the hearing, the court will have to decide to what extent its power of review of the Commander’s decision can go and whether or not it is constrained because of the context (army discipline). It appears to be clear that, substantively, there is great concern over the reasonability of the Standing Order and the manner of its application against the applicants.

Follow us on Twitter (@Follow_SALC) to find out when the judgment will be delivered.